The Truth Will Out: Is Private Equity Overvalued?

Luis O'Shea, Burgiss

Key Takeaways

Burgiss data and novel analytics suggest that, in the aggregate, U.S. Venture Capital funds are currently overvalued, but that U.S. Buyout funds are not overvalued.

This new methodology produces an index of over- or undervaluation based exclusively on the Burgiss Manager Universe (BMU), and is independent of the behavior of other macro variables such as listed equities.

Possible overvaluations may make current allocations to private equity seem larger than they truly are (i.e., the “denominator effect”).

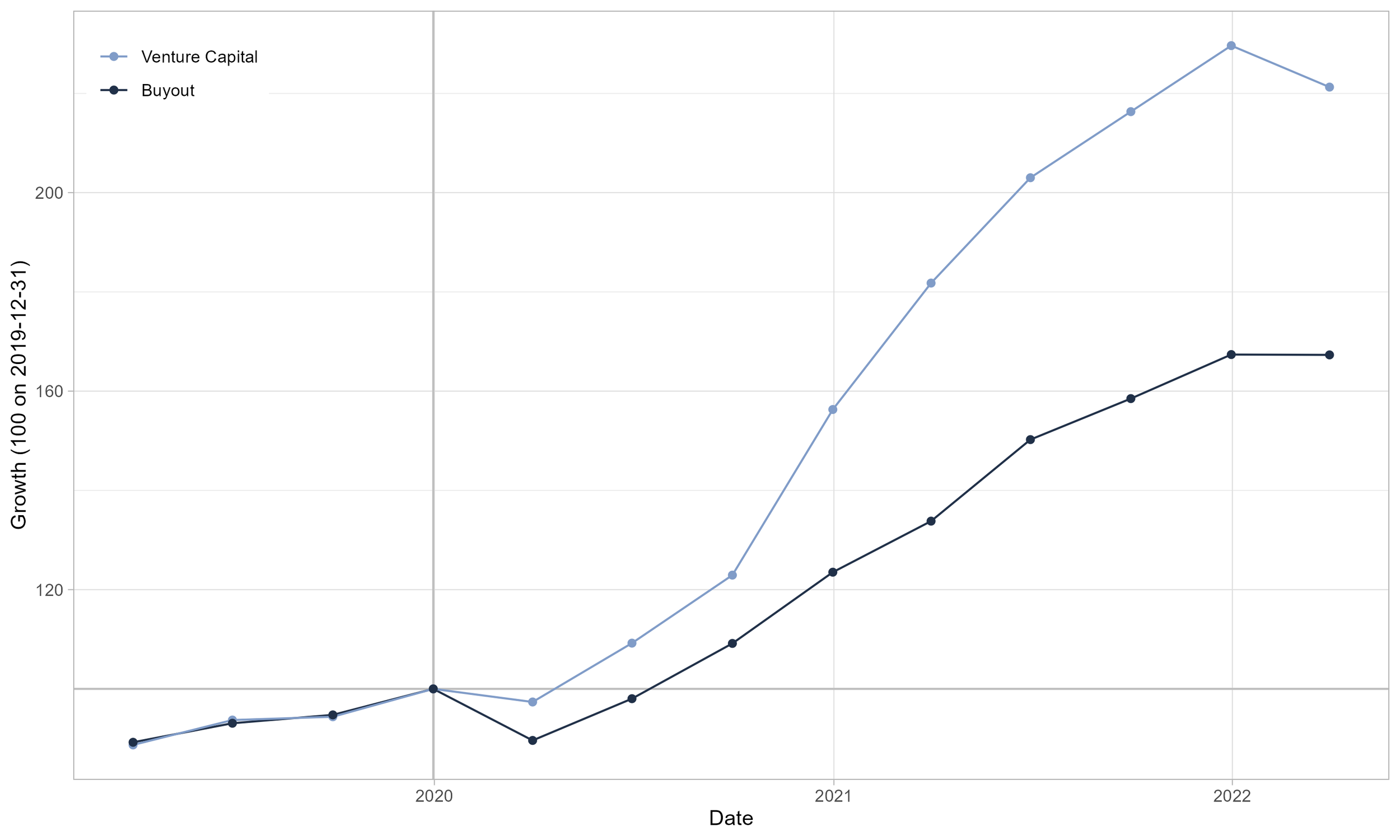

Given the significant recent market moves (see figure 1 for the behavior of private equity), there has been much debate regarding whether the valuations of private equity funds are too high. Part of the concern stems from the two types of lags present in private capital data. First, there is a reporting lag of about three months. Second, reported valuations are subjective, often incorporating lagged sources of data such as comparable transactions, which leads to even further lagging of valuations. After large market moves, this lag causes investors to be unsure of their exposure to private capital, their allocations relative to their targets, and what their expectation of near-term returns should be.

Figure 1: Cumulative returns of Venture Capital and Buyout funds

In other work, we have investigated the lagging and smoothing of private capital data relative to a listed index (see "How Risky Are Private Assets?" and "Estimating Public Market Exposure of Private Capital Funds Using Bayesian Inference"). An understanding of this lag, together with the recent returns of the listed index, provides guidance on whether valuations are currently too high or too low. There is a second approach, however, that relies purely on private capital data. The core idea is to exploit the fact that fund valuations are subjective and may suffer from biases, but fund cash flows are objective, i.e., distributions reveal the true value of assets—The truth will out. We provide a Technical Appendix that details how the cross-sectional variation in fund cash flows allows one to infer the degree of over- or undervaluation of fund assets. The intuition, though, is simple. Suppose we can observe two funds during some quarter, and both have the same return (which we consider to be typical for the asset class). Let’s assume, further, that one fund does not exit from any of its investments (and hence distributes nothing to its investors), while the other exits from some of its investments (and hence makes a distribution to its investors). If all valuations were fair, then the reported returns of the two funds would be equal, but if the assets of the second fund were overvalued, this would depress its reported return. More generally, if assets are overvalued, funds with higher distributions will tend to have slightly lower returns; conversely, if assets are undervalued, funds with higher distributions will tend to have slightly higher returns.

The previous paragraph implicitly defines what we mean by over- or undervaluation, but it bears repeating: we say that a fund is overvalued if the value of its assets exceeds what they could be sold for.

In other words, we focus on the valuation of the assets relative to the fair market value (FMV). Note that sometimes these assets may be sold into the public markets (in the case of an IPO), but sometimes they may be sold to other private equity funds or other investors. Our methodology does not distinguish between these different exit types[1] and is silent on whether the FMVs are themselves too high or too low.

The methodology briefly described above relies on a universe of private capital funds. We use the fund-level[2] BMU (see the Data Summary for further details on this dataset). Even with such a rich dataset, estimating a time-varying valuation bias is difficult and involves some amount of smoothing, which we carry out using spline regressions. Finally, note that the methodology extrapolates from the limited distributions of funds in order to infer a bias across the entire valuation of the fund; on account of this, we feel the index is directionally correct, but its absolute level should be taken with a pinch of salt. Again, see the Technical Appendix for details.

In figure 2, we see the result of applying this methodology to U.S. Buyout and U.S. Venture Capital funds.

Figure 2: Overvaluation index for U.S. Venture Capital and U.S. Buyout funds

The black line is an indication of whether fund assets are over- or undervalued relative to their FMVs. The colored bars correspond to various regimes; the darker color indicates the quarters when the U.S. public equity markets achieved their maximum values, and the lighter color when they achieved their minimum values.

The black line displays the valuation bias, where a positive value suggests that assets of the fund are overvalued. The colored vertical bars represent when public equity markets achieved their maximum and minimum values during various regimes. As documented elsewhere ("How Fair are the Valuations of Private Equity Funds?"[3]), on average, funds tend to have a bias in the direction of somewhat undervaluing their assets. However, during significant market moves this bias swings wildly: currently (as of 2022 Q1) the index suggests that Venture Capital funds are overvalued (relative to their FMVs) but Buyout funds are only slightly undervalued, which is in line with recent history.

Also noteworthy is how this index has behaved during various historical regimes:

Dot-Com Boom and Bust (red): Venture Capital became overvalued shortly after the public markets peaked. The response of Buyout funds was, as expected, much more muted.

Global Financial Crisis (GFC; green): The index behaved in a complementary way to the previous bullet point, with Buyout funds becoming slightly overvalued but Venture Capital funds being less affected.

Start of 2015: Around this time, there was correction in technology stocks, and interestingly, this was reflected in the valuation bias, with a noticeable overvaluation in Venture Capital (and a much smaller effect among Buyout funds).

Current period (2022 Q1): Buyout funds have recently been less undervalued than was typical in the past, but seem to be returning to historical levels. However, Venture Capital is showing clear signs of being overvalued.

In practical terms, the most recent behavior of the index suggests a couple of difficult quarters may be in store for private equity, especially for Venture Capital. In addition, investors should be cautious of a so-called “denominator effect[4],” whereby current fund valuations suggest a larger allocation to private assets than is truly the case.

Further Reading

Burgiss: How Risky Are Private Assets?

Burgiss: Estimating Public Market Exposure of Private Capital Funds Using Bayesian Inference

PERC/IPC: How Fair are the Valuations of Private Equity Funds?

PERC/IPC: Nowcasting Net Asset Values: The Case of Private Equity

Data Summary

The analyses in this article were carried out using data from the BMU with results through 2022 Q1. The BMU is a research-quality dataset with since inception data on over 12,000 private capital funds and funds of funds, representing more than $9 trillion in committed capital across the full spectrum of private capital strategies, including private equity, private debt, and real assets. We used data on over 1,400 Buyout funds and 2,200 Venture Capital funds. These funds generated over 500 individual distribution cash flows per quarter at the start of our sample period, to over double that in recent quarters, thus providing our methodology with the required cross-sectional dispersion in distribution amounts.

Footnotes

[1] The BMU dataset captures the exit type; thus, a topic for future research is whether there is a difference between the bias implied by these two exit types.

[2] The BMU dataset also contains holdings- and security-level data. We may revisit the questions in this blog post using these additional data in the future.

[3] These authors use a similar methodology to estimate a single undervaluation number. In contrast, we explore how it changes over time.

[4] Arguably, it would be more accurate to call this the “numerator effect.”